Ocean Vuong is undoubtedly one of the greatest literary figures of our time. His work has won him accolades from numerous mainstream publications, as well as a host of major awards, including the Mark Twain American Voice Award and the TS Eliot Prize for Poetry.

However, Vuong is so respected for more than just his literary acclaim; as a queer Vietnamese refugee who fled to the United States with his family, Vuong’s heartfelt portrayals of American life are remarkably sensitive and nuanced.

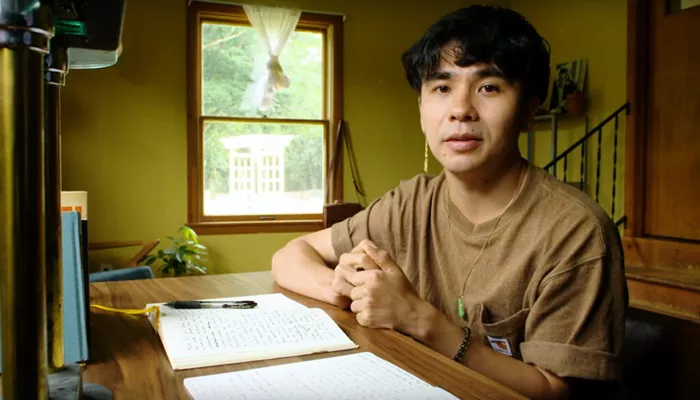

So, as a long-time fan of Vuong’s work, the opportunity to interview him ahead of the release of his latest novel, The Happy Emperor, not only gave me the opportunity to get to know one of my greatest literary inspirations, but also to gain a deeper understanding of his thought and creative process, which makes his work so lyrical, sincere, and human.

We began by exploring the inspiration for The Happy Emperor. The novel, which revolves around an unlikely friendship between Hai, a 19-year-old Vietnamese immigrant, and Grazyna Vitkus, his Lithuanian grandmother who suffers from dementia, displays all of Wang’s trademark qualities: deft prose, an attention to the subtleties of life, and rich, sympathetic characterization.

His answer about the inspiration for the novel is equally poetic: “For me, the novel is a wonderful form because it’s so tolerant of diversity—a poem, especially a lyric poem, can become fragmented if you throw too much into it. I always ask my novels to accommodate too much.”

But one of the core issues I was thinking about was the idea of “progress” that we often ask of novels—which, to me, is an arbitrary imperative. The false premise of “change at all costs” is so heavily promoted in Western narratology.

I wanted to write a novel that had transformation but no change: No one can get a better job, no one can “improve their life,” no one can escape to the city. If you deny all that, what do you have? You have to have characters. You have to have people.

I’m [also] interested in the idea of reciprocity and debt. What do we owe each other? What is kindness without hope? It’s easy to be kind and generous when you have a lot to give, and if you have a lot, this generosity won’t have a substantive impact on your life.

I grew up working class, and I’ve always been interested in how and why people are kind to each other even though their kindness can do little to substantive change in their lives.

I don’t know the answer, but… it became a philosophical question that runs through all my work: What is the purpose of kindness when it’s not rewarded, when there’s no hope around it? What does it do? Does it matter? Is it futile? These are questions that this novel is particularly concerned with.

I pointed out that this idea of “change without change” goes against not only the patterns of the Western literary tradition, but also the myth of meritocracy in the United States, especially the “immigrant narrative.” I asked him if he saw his work as a reaction to this ideology, or a response.

Vuong politely dismisses the idea: “I’m personally very skeptical of total opposition. One of my favorite British theorists, Raymond Williams…is skeptical of work that is always in opposition to power.

I know it sounds like a fantasy, but what he meant is that if you’re always correcting, then you can only ever be a yes-man. You can never make suggestions as an artist. You’re always cleaning up power’s mess.”

In the material world, we can’t help but do that—we have to vote accordingly, we have to fight for our rights, we have to be vigilant against the erosion of civil liberties, as is happening in the United States right now.

But in art, we can; we can have the illusion of asking the first question in art. When I sit down to write, I try to make myself think: What would I say if I could say it the way I want to? What would that look like? Can it really be evaded? We don’t know the answers unless we really try.

“One could argue that because I’m out of the Western dialectic of power, my flesh is intertwined with empire. Whatever I say, I’m in a position to be corrected because my speech is about asserting self-esteem, self-worth, and self-preservation, all of which is unnecessary without power.

So, I’m in a dilemma, but so far in my career, I’ve found myself more fulfilled as a writer when I’ve sat down and asked myself, ‘What do I still have?’”

Vuong’s critique of Western narratology stems from his deep study of Western narratology and his comprehensive understanding of its concepts. This shouldn’t be surprising—Vuong is a professor of modern poetry and poetics in NYU’s MFA program—but it’s interesting to me that so much of his thinking about writing is rooted in literary and critical theory.

In thinking about the narrative convention of “catharsis,” Vuong notes that Aristotle originally conceptualized “narrative” as “a way to relieve the tension of the masses… to get rid of their dissatisfaction with the state or their personal lives; in other words, to get rid of any revolutionary sentiment through catharsis.”

In another conversation, we talked about how to speak to these audiences. “Western literature, especially in the English-speaking world, is very rhetorical,” Vuong argues. “Meanwhile, Japan has Basho—like the haiku poets of the Tokugawa era—and there’s almost no rhetoric. There’s no rhetoric, everything is based on imagery.”

“As a kid in America, I was taught that writing had to be persuasive, that’s what was rewarded. The most persuasive prose and short story poems got the highest marks, got awards, won prizes. I wasn’t interested in persuading people, and it wasn’t until I started reading Eastern poets and learning about their influence that I realized there were other ways to do it.”

Given Vuong’s critical acclaim, I wonder why he’s not interested in persuading people. Clearly, his writing is persuasive and widely read. His first book, a collection of poetry called Night Sky with an Exit Wound, was named one of the best books of 2016 by New York Times critics; it also won him the TS Eliot and Thom Gunn prizes, and three of the poems in the collection won their respective prizes.

His first novel, On Earth We Are Briefly Gorgeous, also won numerous awards and was named one of the best books of the year by major publications including The Guardian, The Wall Street Journal, The New Yorker and The Washington Post. Despite this, Vuong admits that fame has not had the effect he expected.

“I expected this to happen: the pressure of success… can desensitize you. I was waiting for it, and I didn’t mean to be complacent—I think it’s more of a mental defect [for me] than any talent—” Vuong said, “but I was never swayed by public acceptance or success because I wasn’t so tied to my work.”

I think I have a deep connection to this medium, but once the work is done, I don’t want to defend it. They’re like little boats floating down the river: my first book, my second book—they’re just floating down the river.

Some people sprinkle glitter on them, some people throw tomatoes on these little rafts, but that doesn’t matter to me. I think it’s a Buddhist idea, an idea of ”non-attachment”: you are not yourself, you are not your work, you are not your ego.

Feng explains that he doesn’t think he’s naturally ambitious. “I know it sounds a little disingenuous and pompous, given how successful my work has been – I’m not going to pretend that I’m not ambitious. But I never thought of myself as a poet until my teacher came to me and said, ‘I think you could be a poet. You could do this. You could make a living this way.’ I never thought of myself as a novelist until my agent, Frances, got in touch with me… She came to me directly and said, ‘I think you could write novels.’ I never thought of myself as a teacher, and then someone said, ‘You’d make a really good professor, you should try.’ The same thing with playwriting.

And books – they’re ossified. If I think deeply about it, I say, ‘How can you connect yourself to your work?’ Because the work is fixed in time. My last book, Time is Mother, is a collection of my mental photographs from February 2022, when I submitted the final edited version of the book.

So why should I have any strong connection to the past, or why should I be grateful to my past self?

…I feel like I’m driven more by not wanting to disappoint people I look up to than by my own ambition. I used to be really ashamed of that. I thought, ‘Oh my god, I can’t really be considered an artist if my ambitions are that small.’

But now that I think back on it, it’s been pretty productive, and I think I’m more driven by a core of relationships, with people I love and people who believe in me. I want that more than I do as an artist. I used to find that unfulfilling, but now I feel like I’m really proud of it.”

For Vuong, writing is a form of giving, a process that’s perhaps more selfless than most writers can be. This philosophy also extends to his recent debut photography collection, Sống (Song), out in 2024. I asked him why he chose to get into this field; it turns out that Vuong has been taking photos longer than he’s been writing.

I’ve been doing [photography] my whole life, but [as] a private practice. Initially, it was a way for my family, who couldn’t read and couldn’t understand my work, to understand my place and my inner world. I took pictures to show them my perspective, but also to give them an idea of where we lived, because they had very tight work schedules.

They couldn’t go out at 2pm unless it was Sunday; even on Sundays, they worked in nail salons and sometimes on Sundays. It was kind of incredible to me that a lot of my family who worked in factories had never experienced lying down in the park in the afternoon – I know it sounds very, I don’t know, exaggerated, but when I try to describe it, I’ve never seen them do it.

So I was really just going out to show them this place that they were supposed to live in, but there was no phenomenological experience.

“When I met Nan Goldin, she encouraged me to start pursuing photography seriously. Again, it was just her openness, I don’t think there was anything special about me. I think she would say that to anyone who comes to her and says, ‘I’ve been doing photography for 20 years,’ she would just say, ‘You need to be fully present, share, open up.’ So that was just a pattern that happened in my life and career.”

Reflecting on his photography debut with Culture magazine, Vuong also explained that the series of photos was a response to other photography he had been exposed to.

Vuong recalls that, compared to Donald McCullin’s photographs of dead North Vietnamese soldiers, the nail salon photos were perhaps meant to remember and capture “the faces of the Vietnamese who fed me, the faces of the Vietnamese I kissed, the faces of the Vietnamese I wiped their sweat as they worked, the faces of the Vietnamese who were alive.”

I asked Vuong if he chose to post these photos in part because he felt that words were somehow insufficient. He answered without hesitation, “There are times when writing feels completely futile.” But Vuong added, “I think it’s important to allow words to exist.”

Sometimes I wonder, why am I doing this? Actually, I felt that way a week ago. I thought, am I depressed, or have I just lost faith in everything I do? I think that’s okay.

It’s healthy to question the validity of your medium because that’s how you see the medium, right? We ask art makers to make the world clearer.

But I think the most powerful thing about art is that it’s not that “look out the window” gesture, but “look, this is a window.” It’s more effective for an artist to point out the window than to look through it.

Vuong once expressed this sentiment in an interview about photographer Robert Frank. “One thing that’s often overlooked in successful art is courage,” Vuong said. “If you don’t roll the dice, then it’s meaningless. You should constantly question whether what you’re doing is enough.”

All of this seems to come back to this idea of challenging yourself, expanding the medium, pushing the limits of narrative, and resisting power. I went back to Vuong’s idea of “speaking first” and what he really wanted to say—if he could really say it the way he wanted to.

I want to borrow Walter Benjamin’s theory of “dialectical imagery,” which was against Hegel’s dialectic of conflict giving rise to innovation…Benjamin argued that, in fact, revolutionary or radical images are expelled from this dialectic.

It’s a rupture, the spark when you’re sharpening your knife. It’s new possible images, new possible ideas…that are expelled from the dialogue. [This] has the potential to provoke new conflicts and subvert the existing system. I believe this.

I can look at my life this way. I was “expelled” for the Vietnam War—expelled from Vietnam in its entirety. Without the war, I wouldn’t be alive, right? I’m a mistake.

I’m interested in, in a Benjaminian sense, the idea of error and fallacy, the devious lack of a place, as a practice, as a powerful place of creation, rather than a paralysis, error, or futility. I think the idea of being in the wrong place is actually an engine that can inspire people to create.

Vuong’s final response is a perfect example of why his work resonates so well, especially for queer people, immigrants and their children, and other marginalized groups. It’s a call to push back against power, to reclaim some of the private, shared spaces where love, kindness, and generosity can selflessly flourish.

It asks who we are outside of the labels and stereotypes that the West imposes, perpetuates, and sometimes violently enforces. It asks what we could write about if we had the courage to speak up first.